Published July 24, 2025

Sweeping changes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) under the recently passed budget reconciliation package (H.R. 1 also known as OBBBA) —passed by a majority of Republicans in Congress and signed by President Trump on July 4, 2025 — will force states to make tough choices, even before many provisions officially take effect. One early example: Texas has opted out of the Summer EBT Program, which provides nutrition support to school-age children during the summer, citing concerns over future state obligations to fund SNAP as a key reason.

While the most significant SNAP cuts under the act will not begin until after the 2026 midterm elections, state legislatures must start planning now. Delaying action will result in state administrative crises and budget shortfalls once the law is fully implemented.

New Financial Burden for States — Cost-Shift

One of the most damaging provisions is the cost-shift tied to states’ SNAP benefit payment error rates. Beginning in fiscal year (FY) 2028, states will be required to contribute toward SNAP benefit payments based on these error rates. Notably, this measure does not target fraud. Instead, it penalizes states for administrative inaccuracies — often minor mistakes made by caseworkers or recipients navigating a complex system.

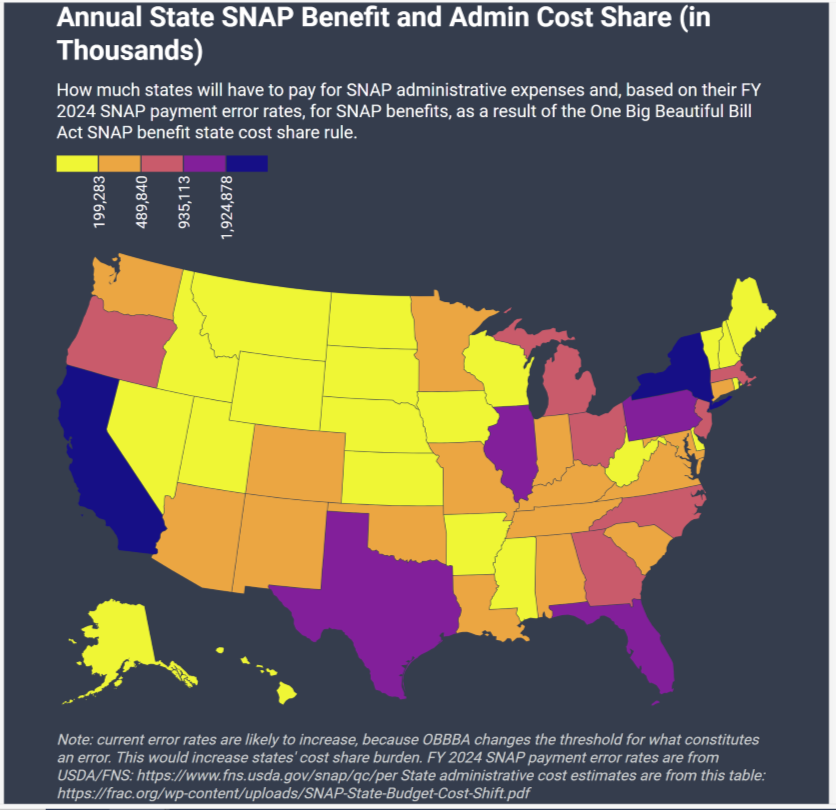

Based on FY 2024 data, 43 states would face new financial liabilities under this provision. Without proactive planning and federal reconsideration, states risk deepening service disruptions and budget stress in the years ahead. See further analysis here.

- Below 6 percent error rate: 0 percent match (not guaranteed; many states have hovered near or above 6 percent)

- 6 percent–8 percent: 5 percent match

- 8 percent–10 percent: 10 percent match

- Over 10 percent: 15 percent match

These rates will be based on FY 2026 data.

To address concerns raised by Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), Senate Republicans added a carve-out allowing Alaska — one of the states with the highest error rates — to delay cost-sharing. To comply with reconciliation rules, the exemption was expanded to any state meeting the 20 percent threshold. As such, if a state’s fiscal year 2025 SNAP payment error rate, when multiplied by 1.5, equals or exceeds 20 percent, the state may delay its cost-sharing obligation until fiscal year 2029. Likewise, if the state meets this threshold in fiscal year 2026, it may delay implementation until fiscal year 2030. However, the delay can be used only once, based on either FY 2025 or FY 2026 data, not both. This structure unintentionally incentivizes states to maintain higher error rates to delay financial obligations.

While presented as a technical fix, the provision was politically driven and structured to secure the bill’s passage. Based on FY 2024 data, states likely to benefit include Alaska, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, and Oregon, along with the District of Columbia.

This is the first time in history that states have had to bear any of the cost of SNAP benefits, and it will hit state budgets hard.

State Cost-Sharing Impact by the Numbers

FRAC estimated the budgetary impact each state can expect to face, based on the latest state SNAP error rates (FY 2024) and the most recent data on SNAP benefits (most of FY 2025, October 2024–April 2025). The most significant costs will be borne by the most populous states, which also have the largest number of SNAP participants. Here are the top five:

State | Cost-Shift Percentage | Estimated Annual Benefits (FY 2025) | State Share of Benefits | Share of Administrative Expenses | Expected Budgetary Impact |

California | 15% | $12.7 Billion | $1.9 Billion | $661 Million | $2.6 Billion |

New York | 15% | $7.9 Billion | $1.2 Billion | $745.7 Million | $1.9 Billion |

Florida | 15% | $7.2 Billion | $1.1 Billion | $205.1 Million | $1.3 Billion |

Texas | 10% | $7.6 Billion | $760.9 Million | $285.4 Million | $1 Billion |

Pennsylvania | 15% | $4.3 Billion | $643.5 Million | $338.7 Million | $982.2 Million |

Every state will feel the fiscal pain of OBBBA shifting costs to states. Eight states would pay none of the cost of SNAP benefits, based on their current error rates: Idaho, Nebraska, Nevada, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Their error rates easily could inch up above the 6 percent threshold and trigger a cost-share by FY 2028, especially with the federal government providing less assistance with administrative expenses. Even if they do not pay any share of benefits, these states still will have to pony up anywhere from $13.9 million (Idaho) to $128 million (Wisconsin) annually.

Every other state will be facing tens of millions of dollars in new SNAP costs, ranging from $24.3 million in New Hampshire to $935.1 million in Illinois. We mapped the fiscal impact of the SNAP benefit cost-shift by state. See how big of a hole OBBBA will carve into your state’s budget when this policy goes into effect. Click here to access the interactive map.

Darker/warmer shades indicate states that will have to pay larger sums when this policy goes into effect.

Additional Administrative Requirements and Costs

The act also slashes the federal match for administrative costs, reducing it from 50 percent to 25 percent beginning in FY 2027 (October 1, 2026), bumping up states’ obligations from 50 percent to 75 percent. This change alone will burden states with a significantly higher share of expenses — especially problematic given that outdated technology and understaffing already contribute to rising error rates. Rather than helping states modernize systems or improve staffing, the law compounds administrative complexity with a host of new mandates. With rising administrative costs and shrinking federal support, many states risk sliding into higher cost tiers.

Key among those mandates is the immediate expansion of time limits. States must now enforce stricter rules on SNAP recipients ages 18–64, including groups previously exempt under the 2023 Fiscal Responsibility Act: veterans, individuals experiencing homelessness, and former foster youth. Agencies must identify and monitor these populations, increasing administrative workload and likely triggering a cycle of benefit loss and reapplication, commonly known as “churn,” that raises costs and harms stability for vulnerable households.

The act also imposes severe restrictions on noncitizen eligibility. Refugees, asylees, and trafficking survivors — who have long qualified under federal law — are now excluded from SNAP, unless they fall into a narrow set of exceptions. States must identify these populations and terminate their benefits, adding another layer of complexity and burden. Additional provisions limit the ability of states to factor internet, and fuel assistance for some populations, into SNAP benefit calculations, disproportionately affecting families with low incomes in high-cost areas. The law also eliminates SNAP-Ed nutrition education funding beginning in FY 2026 (October 1, 2025), triggering layoffs and removing a key support for health education and outreach. For further analysis of the provisions, see here.

The Cost of OBBBA Is Too High for SNAP and States

Taken together, these provisions represent an unprecedented cost-shift from the federal government to the states, one that forces local leaders to make painful tradeoffs between essential services and rising administrative demands. As states grapple with tighter budgets, reduced federal support, and growing caseload complexity, the core promise of SNAP — as a reliable safeguard against hunger and hardship — is at risk. The Trump- and Republican-passed budget reconciliation bill, OBBBA, not only weakens a cornerstone anti-poverty program; it reshapes the relationship between federal and state governments in ways that could prove devastating for millions of families, workers, and communities across the country.

Call to Action:

Anti-hunger advocates should schedule appointments with their Members of Congress now to engage them over the August recess and to highlight the state and local impacts of the SNAP cost shift provisions.