August 24, 2022

This season marks the five-year anniversary of Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria that hit the United States hard and gave rise to major recovery operations, including on the food relief front. There are some clear lessons from those operations that can inform disaster preparation and recovery efforts in the future.

- Lesson One : The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program’s (SNAP) design allows it to respond quickly and effectively as need increases, whether due to an economic downturn or disaster. SNAP is an entitlement program: So long as people meet SNAP’s qualifications, benefits are available for them. Similarly, for households not participating in regular SNAP, states can get permission to offer them short-term Disaster SNAP (D-SNAP) benefits under relaxed eligibility rules. U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) administrative D-SNAP toolbox also allows granting waivers for purchase of hot prepared foods and issuance of federally-funded supplemental benefits for regular SNAP participants in the affected areas.In all, after the 2017 hurricanes, 3.2 million households in Texas, Florida, and the U.S. Virgin Islands were served through D-SNAP and/or supplemental SNAP benefits.[1] In contrast, in Puerto Rico, where the Nutrition Assistance Program is a block grant instead of the SNAP entitlement, nutrition aid was capped and could not expand without congressional action.[2] Currently, legislation pending in Congress (H.R. 4077) would provide equity and pathways to Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands to operate regular SNAP, which also would allow them to tap D-SNAP in event of disaster.

- Lesson Two: Getting eligible people connected to SNAP prior to a disaster allows them to be served seamlessly with supplemental benefits. States can request permission to issue those supplements directly onto the existing Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) cards of SNAP households in affected zip code areas. This obviates the need for those households to go through the D-SNAP enrollment process that is entailed for households not already participating in regular SNAP. Most recently, USDA authorized Kentucky to operate D-SNAP and issue automatic replacement benefits to aid household hit hard by recent flooding.[3]

- Lesson Three: Experience from Hurricane Irma and during COVID-19 shows that using technology for conducting D-SNAP enrollment can lessen the burdens on both D-SNAP applicants and state agency systems. After Irma, the D-SNAP enrollment process in Florida stretched out over many weeks, with long lines at sites. For example, on one day in October 2017, approximately 50,000 people lined up for D-SNAP in Miami.[4] The burdens were particularly severe for those who were elderly or had disabilities. In 2017, litigation on their behalf led USDA to grant Florida limited authority to replace in-person D-SNAP interviews with telephone interviews. Since then, during COVID-19, social distancing constraints led to greater use of remote D-SNAP enrollment operations.[5] Remote enrollment for D-SNAP should continue to be allowed going forward.

- Lesson Four: D-SNAP and supplemental benefits help boost area economies during disaster recovery. Local infrastructure and businesses are often disrupted by disaster and may have long roads coming back.[6] SNAP is one ingredient in building up the economic strength of the community as benefits flow through food retail outlets. Each $1 in SNAP during a downturn generates between $1.50 and $1.80 in economic activity.

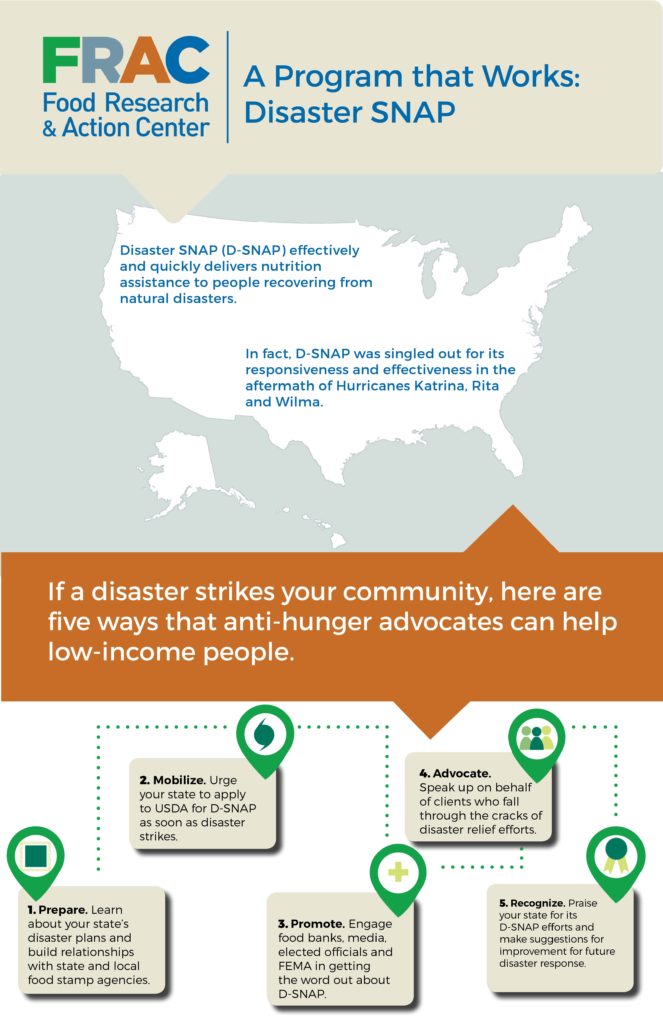

- Lesson Five: Information, outreach, and advocacy matter. The D-SNAP toolbox is that — a set of tools that are available but are not triggered automatically. Even after a presidentially declared disaster, it is up to states to request D-SNAP, supplemental benefits, and other relief for their residents hard hit by a disaster.

As President Biden has pointed out, it is important for states to understand what federal relief they can tap into.[7] Where states are slow to act, community groups can advocate for them to seek relief. They also can advocate for relief that is commensurate with the need. And community groups can partner with states in conducting outreach and educating the public about where and how to obtain D-SNAP resources.

Check Food Research & Action Center’s (FRAC) disaster page https://frac.org/disaster for updates on D-SNAP developments and read FRAC’s An Advocate’s Guide to the Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (D-SNAP) for strategies on leveraging federal nutrition resources during disaster recovery.

[1] At p. 4, https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/d-snap-advocates-guide-1.pdf

[2] At p. 18 https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/d-snap-advocates-guide-1.pdf

[3] See USDA Food and Nutrition Service,, “Kentucky Disaster Nutrition Assistance,” Aug. 19, 2022, https://www.fns.usda.gov/disaster/kentucky-disaster-nutrition-assistance

[4] See Jim Hayward, “NEW: 50,000 line up in Miami for Hurricane Irma food stamps; PB County starts Tuesday,” The Palm Beach Post, Oct. 16, 2017, https://www.palmbeachpost.com/story/weather/hurricane/2017/10/16/new-50-000-line-up/7128301007/

[5] See Atlanta Community Food Banks, Food Research & Action Center, The Food Trust, and Propel,“SNAP in the Southeast: Putting Food on the Table During the Pandemic and Beyond,” at p. 12, https://www.acfb.org/wp-content/uploads/SE_SNAPGap_reportFINAL_HR21.pdf (D-SNAP lessons learned from officials in Alabama and Louisiana during COVID-19)

[6] For background on economic costs of disasters, see U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Natural Disasters: Economic Effects of Hurricanes Katrina, Sandy, Harvey and Irma,” GAO-20-633R, Sept. 10, 2020, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-633r

[7] See White House, “Remarks by President Biden After a Briefing on the Federal Response to the Severe Weather that Impacted Several U.S. States,” Dec. 13, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/12/13/remarks-by-president-biden-after-a-briefing-on-the-federal-response-to-the-s=evere-weather-that-impacted-several-u-s-states/ See also Ellen Vollinger, “It’s Important to Let Those Recovering From Disasters Know All the Aid They Can Request,” FRAC Chat, Food Research & Action Center, Dec. 15, 2020, https://frac.org/blog/recovering-from-disasters-aid