This is a guest post by Janet Poppendieck, Professor Emerita of Sociology at Hunter College, City University of New York, co-founder of the New York City Food Policy Center at Hunter College and senior fellow at the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute at the CUNY School of Public Health and Health Policy. She is the author of several books, including Free For All: Fixing School Food in America, which received the 2010 Book of the Year award from the Association for the Study of Food and Society.

It’s National School Breakfast Week! There’s no better time to look back at the 50-year history of the School Breakfast Program (SBP) to see how far we have come, and what we still need to do to make sure that no child starts the school day hungry.

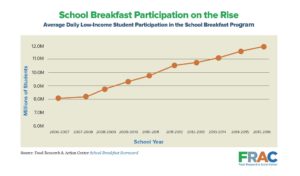

Over the last half century, growth in school breakfast participation has been remarkable. Participation in the SBP, measured as Average Daily Participation (ADP) rose from about 80,000 in the pilot projects in the program’s first year of operation to more than 14.5 million in fiscal year 2016. Over 12 million of the students participating were eligible for free or reduced-price school meals.

Average daily participation has risen every year since the program’s beginning, except for 1982, when the cuts legislated by the 1981 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act took effect[i]. We know there is still much work to do to ensure that all children that need it have access to school breakfast, but this seems to me a remarkable record.

There have been challenges along the way. The two biggest include getting schools to participate in the program, and making breakfast fully accessible by removing the obstacles that prevent students from taking part.

When FRAC first started working on school breakfast in 1971, five years after the SBP was established as a pilot program in 1966, only 6,600 schools were participating, about 8 percent of the 80,000 schools in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP). FRAC conducted a study of the SBP to assess its impact and to identify the obstacles to its expansion.[ii]

FRAC found, in short, that schools were deterred from participation by three aspects of the pilot program design:

- the priority placed on schools in areas with poor economic conditions deterred many schools from participating;

- inadequate funding, especially a prohibition on covering labor costs; and

- the “pilot” status restrictions of the program.

The first phase of school breakfast activism concentrated on reversing these limitations. Congress made the program available to all of the nation’s schools in 1972, and implemented what is called performance funding for both the SBP and NSLP in 1973. Under performance funding, the federal government reimburses schools at established rates for each meal served, as long as the meal complies with federal nutrition and other standards. There are no caps or waiting lists. Performance funding—providing a reimbursement for each meal served—has been the key to SBP’s expansion. Congress also removed the restriction on labor costs in 1973.

School boards and administrators worried that the SBP’s “pilot program” status meant that Congress might defund the program at any time, leaving them with a popular program and no federal funds to continue it. As FRAC wrote in 1972, the “political onus of terminating a popular program …is considerably greater than that of not initiating one.”[iii] FRAC’s 1972 report recommended that the program be officially designated as a permanent program, and Congress took that action in 1975.

Even after these changes were made, it still remained a challenge to get the word out to school boards and communities. In today’s world of instant communication, it may be difficult to imagine the scope of this task. FRAC launched its School Breakfast Campaign to undertake the massive task of making states, cities, and school districts aware of their rights under the new laws and to help them overcome the resistance of school administrators toward participating in the SBP.

The pattern described here — research to identify barriers, legislation to reduce or eliminate these barriers, tracking the implementation of the legislation, and informing and community organizing to help communities learn about and claim their rights —has been a recipe for achievement that has been repeated throughout the history of the School Breakfast Program.

Once the major federal barriers were eliminated, advocates’ attention turned to the state and local levels. State mandates requiring schools in districts with high concentrations of poverty or districts in cities of a certain size to offer the breakfast program became an important tool. The mandates were effective in the states that adopted them, and progress was steady, but slow. By 1990, just under 44 percent of the public and private schools that offered the NSLP also offered the SBP.[iv] Congress addressed this slow growth in the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 1989 by providing special grants to the states for SBP start-up funds, but these would help only if states applied for them.

To learn how advocates overcame obstacles to school breakfast accessibility, read part two of the history of school breakfast.

[i] Kenneth Hanson and Victor Oliviera, How Economic Conditions Affect Participation in USDA Nutrition Assistance Programs, economic information bulletin 100, (Economic Research Service, USDA, September 2012), p. 28.

[ii] Food Research & Action Center. If We Had Ham, We Could Have Ham and Eggs…If We Had Eggs: A Study of the National School Breakfast Program. 1972.

[iii] Food Research and Action Center, If We Had Ham,…p. 73.

[iv] Calculations by Jan Poppendieck based on data provided by the Food and Nutrition Service, USDA. via e-mail, August 26, 2016. Data from National Data Bank version 8.2 public use.