Published August 25, 2025

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is one of the most effective tools the U.S. has to reduce hunger and support households with low incomes. Nowhere is this impact more critical than in rural America, where food insecurity, economic stagnation, and limited access to services intersect to create deep vulnerability. Yet, provisions in the recently enacted budget reconciliation law (H.R. 1, also known as OBBBA) — passed by a majority of Republicans in Congress and signed by President Trump on July 4, 2025 — undermine this vital program, hitting rural communities hardest, economically, socially, and physically.

Rural Realities: Higher Need, Limited Resources

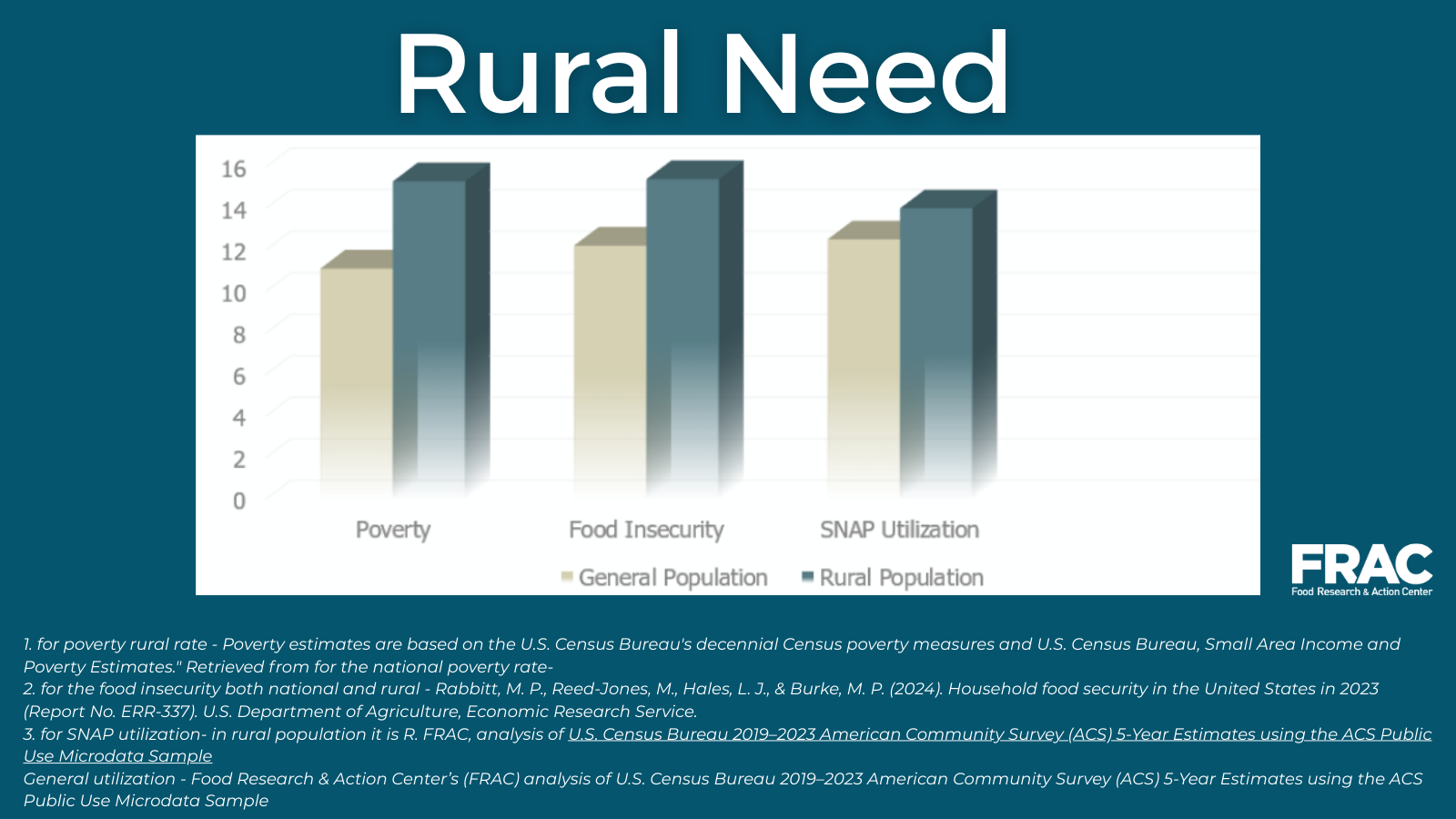

Rural America continues to face significant and persistent challenges. While 11.1 percent of the U.S. population lives in poverty, that number climbs to 15.3 percent in rural areas. Similarly, food insecurity affects 12.2 percent of the general population, but 15.4 percent of rural households. One in seven rural households relies on SNAP, compared to one in eight in metropolitan areas.

These elevated rates reflect deeper structural issues: limited job opportunities, aging infrastructure, higher costs of living, and a shrinking share of the national economy. From 2019 to 2023, real GDP growth in rural areas averaged just 1.8 percent per year — below the national average of 2.4 percent. By 2023, rural counties accounted for only 7.8 percent of national GDP, continuing a two-decade trend of decline.

While federal investments led by the Biden administration, including the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act, attempted to tackle this issue, it will take years to yield widespread economic gains. In the meantime, rural communities remain vulnerable, especially as key industries like agriculture, mining, and manufacturing shrink due to automation.

SNAP as an Economic Stabilizer

SNAP is not only a poverty alleviation tool — it also acts as a powerful economic multiplier. Every $1 in SNAP benefits generates up to $1.80 in economic activity. In rural America, where small businesses operate on thinner margins, that support is often the difference between staying open and closing down.

This is particularly true for local grocers. In many rural towns, the local grocery store is the sole food retailer and depends on SNAP transactions to remain financially viable. When SNAP is cut, grocers experience an immediate loss of revenue. As these small retailers struggle or shutter, communities lose critical access points for healthy food. This creates a downward spiral: Fewer stores lead to more U.S. Department of Agriculture-designated low-income low-access areas, less local economic activity, and ultimately, reduced local and state tax revenue.

Recent analysis highlights the acute risks SNAP cuts pose to rural communities. Of the 303 counties identified as having both high SNAP participation and limited access to authorized retailers, 77 percent are rural, despite rural counties comprising only 62 percent of all U.S. counties. These areas sit at the intersection of high-need and low- access, where SNAP recipients rely on a limited number of local retailers for food.

In these rural counties, small grocery stores, specialty shops, and farmers’ markets are at heightened risk. These retailers serve as economic anchors, and SNAP cuts not only jeopardize food access but also slash revenue for local businesses, destabilizing rural economies and shrinking already strained tax bases just as demand for public services grows.

How H.R. 1 Will Harm Rural Communities

The new law introduces multiple changes to SNAP that threaten to intensify rural hardship. While all of the provisions are concerning, three stand out as especially harmful: expanded time limits, increased administrative costs, and new food benefit cost-sharing requirements.

1. Expanded Time Limits and Work Requirements

Section 10102 significantly expands SNAP’s time limits for Able-Bodied Adults Without Dependents (ABAWDs). It extends the three-month benefit cap to:

- adults up to age 65;

- parents of children aged 14 and older; and

- individuals who are homeless, veterans, or former foster youth.

These changes fail to account for the structural challenges of rural labor markets, where economic opportunities and social supports remain limited. Rural areas consistently face higher rates of part-time employment, fewer job openings, and limited access to child care and transportation — all of which hinder compliance with stricter SNAP work requirements.

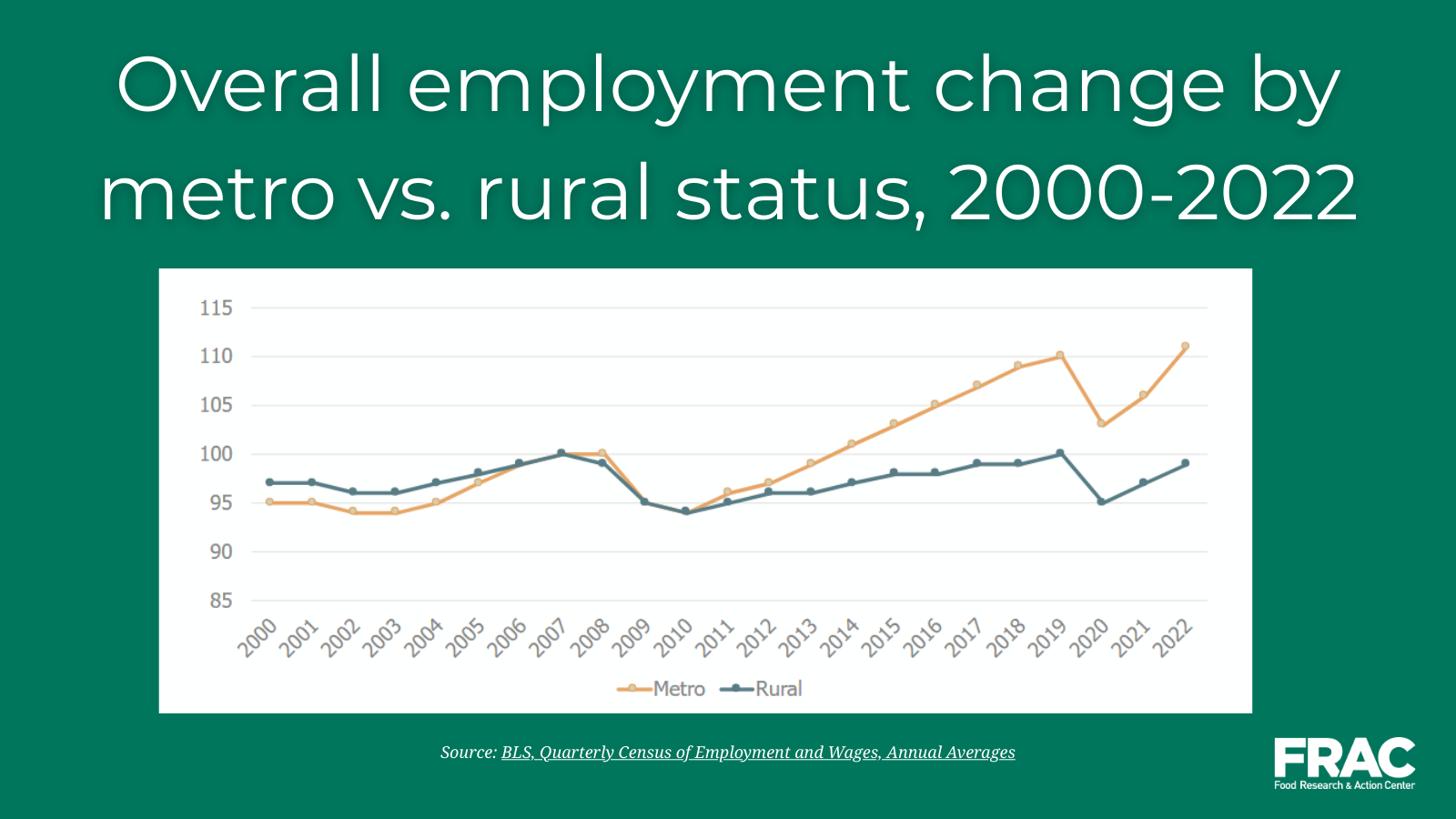

From 2019 to 2023, rural job growth averaged just 0.3 percent per year — well below the national rate. By 2023, nearly half of rural counties had yet to recover pre-pandemic employment levels. More broadly, rural areas have faced persistently slow job growth over the past two decades, with many still below their pre-Great Recession employment levels even before the COVID-19 pandemic began. See graph.

Part-time rural workers are especially vulnerable under the expanded time limits. In 2023, they were more likely to be among the working poor compared to their urban counterparts. Notably, many rural residents work part-time due to non-economic constraints — such as caregiving responsibilities and lack of affordable child care — rather than a lack of available full-time jobs.

For example, among rural working poor age 25 to 54, 14.6 percent cited child care problems as their primary reason for part-time work in 2023, while another 25.5 percent pointed to family or personal obligations, including elder care. Among those ages 55 to 64, 37.8 percent reported family responsibilities as their primary reason for part-time work, and 27.2 percent cited health or medical limitations.

Compounding this challenge, access to child care in rural communities has declined. Between 2017 and 2022, the number of rural child care providers fell — particularly in small towns and rural-adjacent areas — further limiting parents’ ability to meet work requirements.

Together, these structural barriers mean that many individuals will lose SNAP benefits not because they no longer need assistance, but because they are unable to meet inflexible work rules that do not reflect the realities of rural life.

2. Increased Administrative Costs

Under Section 10106, the federal government will reduce its administrative match rate from 50 percent to 25 percent starting in fiscal year (FY) 2027. That means states, and in some cases, counties must cover a larger share of SNAP’s administrative costs.

In 10 states, including California, Colorado, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Virginia, and Wisconsin, counties administer SNAP, collectively investing $1.7 billion annually in program administration. With a 25 percent increase in non-federal administrative matching, costs could rise by $850 million, surpassing $2.5 billion annually.

This burden is particularly hard to bear in rural counties where tax bases are shrinking. As SNAP cuts lead to grocer closures and reduced local spending, rural governments may have to raise taxes or cut services, just to administer a program in which benefits are simultaneously being cut. It is a lose-lose situation for both governments and residents.

3. SNAP Food Benefit Cost-Sharing

While most states passed budgets relatively smoothly in 2023 and 2024 by relying on surplus revenues and remaining federal COVID-19 relief funds, the fiscal outlook for 2025 became more challenging. Slowing revenue growth, rising costs of core services, and the fiscal impact of federal policy in the reconciliation process created mounting budget pressures. In FY 24, most state budgets were allocated across Medicaid, K–12 education, higher education, transportation, corrections, public assistance, and a broad “all other” category that encompasses the bulk of state agencies, with K–12 education and Medicaid making up the two largest areas of state spending.

As the federal budget reconciliation process advanced, states had to prepare for the fiscal consequences of the Republicans’ agenda to dismantle both SNAP and Medicaid, making already difficult budget decisions even harder. For the first time in history, states also had to plan for possible contributions to SNAP benefits — a brand-new state budget item costing millions of dollars — while simultaneously planning to absorb major federal cuts to Medicaid, already one of the largest areas of state spending. As a result, many states made difficult choices this budget season as they confront structural deficits rather than temporary shortfalls.

Looking ahead, the burden will only grow. Under Section 10105, states must begin sharing the cost of SNAP food benefits in FY 2028, with required contributions tied to their payment error rates. For example, states with error rates below 6 percent will face no match, while those between 6 and 8 percent will pay a 5 percent match, those between 8 and 10 percent will pay 10 percent, and those over 10 percent will pay 15 percent. Based on FY 2024 data, more than 40 states would already face cost-sharing obligations, and even states currently below the 6 percent threshold could easily move into higher brackets over time. Compounding the pressure, states must continue payments even if their error rates later improve. Further information on cost share can be found here.

Together, these changes represent a dramatic shift in SNAP’s financing structure. Rather than strengthening program integrity, the cost-sharing model imposes significant new financial burdens — particularly on rural and under-resourced states — while threatening to reduce access for eligible families. By forcing states to absorb millions in new costs or cut eligibility, it undermines SNAP’s role as a federally funded support designed to respond to need, especially during economic downturns.

The High Stakes for Rural America

SNAP has long served as a lifeline for rural America. It reduces hunger, stimulates local economies, and improves public health. The cuts and structural changes in H.R. 1 turn this proven support into a liability — one that rural families, grocers, and local and state governments are ill-equipped to bear.

H.R. 1 undermines this lifeline. By expanding time limits, increasing administrative costs for states and counties, and introducing unprecedented food benefit cost-sharing, the law imposes millions in new obligations on governments already facing shrinking revenues and structural deficits. For rural states and counties with smaller tax bases, these costs will force difficult trade-offs: raising taxes, cutting essential services, or restricting SNAP eligibility at the very moment when economic conditions demand greater support.

SNAP’s design as a federally funded, countercyclical program ensures it expands when families and communities need it most. Preserving this structure is essential. Policymakers must act to reverse these damaging provisions; advocates must raise awareness of their impact; and community leaders must continue to push for policies that protect access to food and economic stability. Without urgent action, rural America will face deeper hunger, weaker economies, and growing inequality.