August 27, 2024

Millions of college students will return to campus worrying about hitting the books on an empty stomach.

A recent report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) highlights the prevalence of food insecurity among college students and underscores the critical role that the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) plays in supporting student success.

Food Insecurity on College Campuses

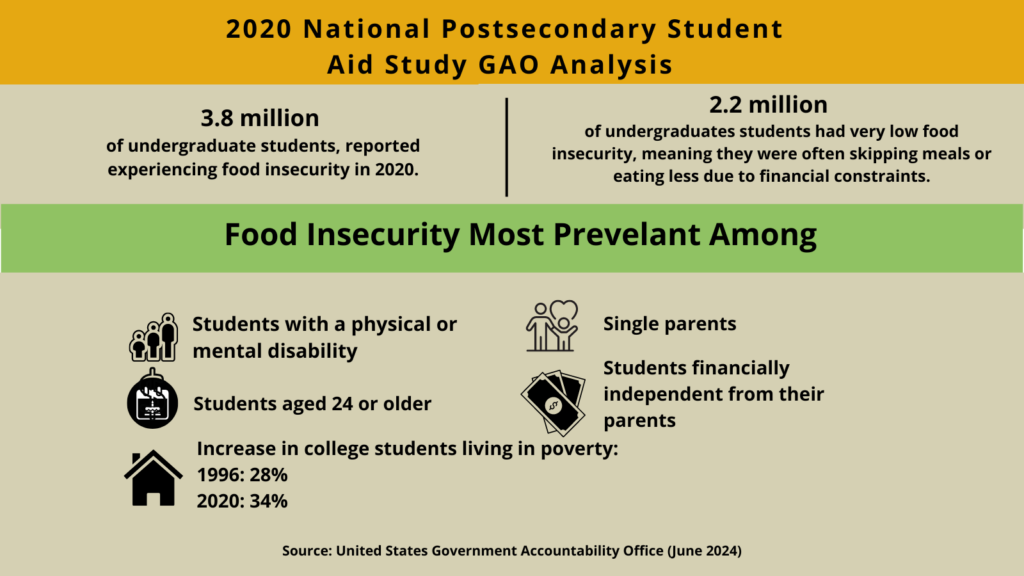

In an analysis of the 2020 U.S. Department of Education National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) data on food insecurity among students, GAO found that 3.8 million, or 23 percent of undergraduate students, reported experiencing food insecurity in 2020, more than twice the rate of food insecurity among the U.S. population that year.

Additionally, GAO found that:

- Most food-insecure students (2.2 million) had very low food insecurity, meaning they were often skipping meals or eating less due to financial constraints.

- Food insecurity was more prevalent among students with the following characteristics: had a disability, were 24 years old or older, single parent, or were financially independent from their parents.

- More college students today are from households with low incomes, with 34 percent from households at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty level in 2020 compared to 28 percent in 1996.

A wide range of research has demonstrated the adverse effects of food insecurity on students’ physical and mental health, as well as academic success.

Too Few Eligible College Students Access SNAP

Millions of college students nationwide rely on SNAP to access food to fuel their health and learning. SNAP has a positive impact on students, including increasing food security and improving health while easing financial worries, allowing students to focus on their studies.

Despite its effectiveness, only 33 percent of students identified as potentially eligible for SNAP reported that their households received SNAP benefits. A troubling note is that fewer than 2 in 5 food insecure students were deemed potentially eligible.[1]

Addressing the barriers to college students’ access to SNAP will make a big difference in reducing student food insecurity. Current SNAP eligibility rules for college students are needlessly complex, creating additional barriers for students seeking SNAP. These barriers continue to exacerbate inequities for college students experiencing food insecurity. Primary among these challenges is the “work-to-eat rule” — Students who do not meet any other exemptions must work 20 hours a week through a work-study program or other paid job to be eligible.

During the pandemic, Congress temporarily expanded SNAP eligibility to students whose Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) indicated they were eligible for federal- or state-funded work-study, regardless of participation; and to students who had a $0 Expected Family Contribution (EFC). However, these flexibilities expired in the summer of 2023.

By permanently expanding SNAP eligibility to those with $0 EFC, the GAO found an additional 1 million students would be potentially SNAP-eligible.

How to Connect More College Students to SNAP

The U.S. Department of Education has communicated that both institutions of higher education and state grant agencies can conduct targeted email outreach to students who may be eligible for means-tested public benefits programs like SNAP. Students would be selected for outreach based on their FAFSA data, Pell Grant status, and Student Aid Index, which replaced the Expected Family Contribution in recent changes to the FAFSA. Additionally, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has communicated that states should prioritize college students in SNAP outreach efforts.

As the federal government continues to confirm the need to connect students to SNAP, policymakers, schools, and other anti-hunger stakeholders must do more to ensure students can focus on their hunger to learn instead of being hungry.

- Institutions of higher education must widely advertise the benefits of SNAP to students, faculty, and staff across campus. These awareness campaigns should aim to reduce stigma related to food insecurity and accessing benefits. If the student is visiting an on-campus food pantry, the student should be pointed towards resources to support them in accessing SNAP. Some institutions have found success in creating student application assistance resource hubs in partnership with SNAP state or county agencies or anti-hunger organizations.

- State SNAP agencies must continue to engage in and support outreach efforts to college students. This includes screening students for exemptions, clarifying complex eligibility options, and engaging in data sharing that can help identify potentially eligible students. SNAP agencies should also explore opportunities to be on campus during college orientations, during the first weeks of classes, to inform students about federal nutrition programs assistance available to them.

- For example, this flyer, designed by the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute (MLRI), provides a clear overview of college student eligibility rules and directs them on how to apply for SNAP. Similar resources can be adapted for other states and shared with students to increase awareness of SNAP.

- USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service must continue to:

- Push for further guidance and support to ensure that students are aware of their potential eligibility for SNAP and how to navigate these systems: Clear communication, targeted outreach, and accessible resources are essential to empowering students and facilitating their access to critical benefits.

- Facilitate equitable access to SNAP for college students by encouraging state SNAP agencies to implement thorough screening of exemptions.

Take Action Today: Urge Congress to Pass the EATS Act

Congress has a role to play in supporting students’ well-being by passing The EATS Act. Through this bill, students’ eligibility would no longer be tied to participation in work-study, working an additional 20 hours of paid work outside of class, or verifying another exemption, which would ensure that no student with low income falls through the cracks.

By leveraging lessons learned from pandemic-era SNAP flexibilities and responding to evolving need for the program, we can create a more supportive environment for students to learn, to grow, and ultimately, to use today’s nutrition resources to fuel their futures.

[1]The data from the GAO report suggests that the 3 in 5 food-insecure students were not flagged as potentially eligible for SNAP because they did not meet the strict criteria used to determine eligibility. These criteria include specific student exemptions like working 20 hours per week or participating in work-study. Additionally, the analysis relied on income thresholds of 130% of the federal poverty level and does not account for students in states with higher income thresholds through BBCE.